Improving How Universities Teach

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

While I was working on a much more technical first post, Nature released a News article on a core raison-d’être of this blog: the trust of public in scientists, scientist engagement with policy making, and their involvement with society. So, let’s take this opportunity to delve into this topic.

The Nature News was prompted by a new pre-printed article where researchers led by Viktoria Cologna (University of Zürich) conducted extended interviews and data analysis on the “Trust in scientists and their role in society across 67 countries”.

For those unfamiliar with pre-prints, these are scientific articles distributed openly before peer-review, the process usually required for formal scientific validation. Despite lacking validation by the scientific community, pre-prints facilitate access to research for anyone interested, thereby lowering barriers to scientific development globally and fostering transparent communication with non-experts (as articles would otherwise be behind paywalls). Several servers for pre-prints exist; the most famous among the physical sciences community is known as the arXiv. I hear biologists tend to use the bioRxiv.

Let’s look at some key points of the work:

Points 3-5 catch my attention. So let me explore them further.

On point 3, the authors promote a list of recommendations including: promoting more transparent practices regarding funding and data sources, and investing more in public communications. Since scientists are seen as not particularly receptive to non-specialist views on their subject-matters, the authors recommend avoiding a top-down approach. They advocate for public participation via genuine dialogue.

I wonder what venues could be used for that? In my experience, science museums provide a great venue for this kind of engagement (if you are in the area, the Boston Museum of Science is great!), but perhaps tend to be a wee too focused on younger audiences. Maybe universities and publicly funded labs (like American Federally Funded R&D Centers - “FFRDCs”) could host “open-house” events for the public more often? I wonder if promoting some “ask your friendly neighborhood physicist” - or whichever scientific specialization! - event at a local library could become a thing. With canapés? I hear Astronomy on Tap are also great events.

On point 4, the authors are a bit roundabout

”[minority mistrust] may affect considerations of scientific evidence in policymaking, as well as decisions by individuals that can affect society at large.”

We can be a bit more explicit - of course, no judgment on different opinions - and name some examples of what they may have meant: policies where the attitudes of few can cause exponentially broader effects include vaccination and mask use during a pandemic. Situations where the voice of minorities take disproportional size in policy making include the effect of hate discourse that at times empowers extremist governments. The effect of policymaking in science is a reality for me and many of my friends, who have been living through the “Brazilian scientific diaspora” of the past 10-20 years (yes, this is a thing! If you have not heard of it, read more here).

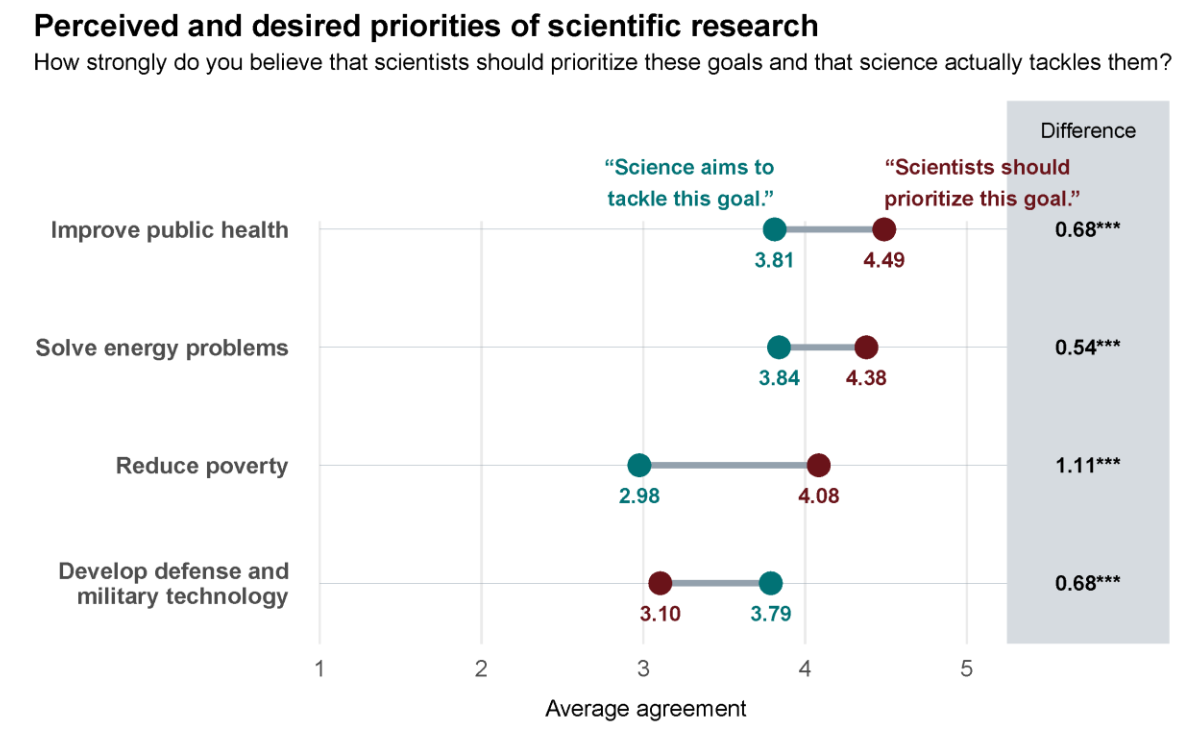

Point 5 raises more intriguing questions. The conclusions for this point are based on Figure 5 of the paper. Let me reproduce it:

This graph showcases the difference in perception the public has on “what science aims at” as a research topic and “how much should it prioritize” the given topic. Four subjects are considered: healthcare, energy, poverty reduction, and military/defense.

A first question comes to my mind: how much society prioritizes and is interested in simple discovery? Unfortunately, the plot above misses the topic of non-applied scientific inquiry. That is what drives the majority of my colleagues in the physical sciences, at least. While of little direct social relevance, at first sight, this topic contributes to people’s “cultural welfare”. Looking at the stars and knowing that Earth is not the center of the universe has had profound impacts in society (at least regarding Western society, I guess we can say). Learning that genes encode many of our traits is important for predicting and treating genetic disorders, but it also gives us a better sense on ethical decisions and our general ability to deal with our personal similarities and differences. These pieces of knowledge affect our homes, families, and how we deal with each other. I would be very curious to see how an extended statistical analysis would position the matter in reference with the others in Figure 5.

Now, are scientists engaged enough in policymaking and working too much in military applications? I guess the answer depends on the country, as the authors also hint, and these points may be somewhat related. In the USA, agencies traditionally related with science (NSF, DOE, DARPA, IARPA) have open and constant channels of communications with researchers, both public and private. Only agencies like DARPA and IARPA do have defense applications as a priority. Direct connections with congress people and senators is perhaps a bit rarer in my experience. I have seen it happen if personal contacts exist, but building those channels is not easy.

I have been terribly lucky in my past few years at Boston, as there is a strong community of thinkers in the area. Events promoted by Science Technology and Society (at times known as STS) clubs and students at Harvard and MIT have been helping me bridge science and policymaking, introducing players and consultants that work directly or indirectly in D.C.. On the other hand, a recurring theme, reinforced by my acquaintances more closely associated with active members of the federal government, is the challenge of capturing their attention with topics considered non-immediate. This is particularly true for subjects unrelated to defense. So in the case of the USA, if there is a public perception that scientists have been prioritizing defense activities too much, perhaps this could be a result of political pressures.

On a bright side, my experience with local government has been quite positive! I have seen, and participated in, several public-private science-centered initiatives to promote economic development. This kind of work may, perhaps, help diminish the gap between “science aim” and “scientists priority” in what regards reducing proverty. Of course, similar initiatives exist at the federal level as well, particularly focused on manufacturing of tech (which I guess always require strong scientific foundations).

Perhaps my alignment of interests makes this a self-serving satisfaction, but I am happy to see this subject being advanced by hard data-driven scientific work! So I will leave my sincere appreciation to Dr. Cologna and her collaborators, and wish them all luck with their refereeing process, which will undoubtedly enhance the scientific value of their work.

I should also thank my wife, for pointing out to me the Nature News in the first place!

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

Back to book reviews! The backlog is growing!

This post is a long one in the making. I should dedicate it to my wife, as this has been a family project running for years. We will divert from science mana...

Short post inspired by a big lesson. Recently I was in a conference and me and other scientists were discussing how easy or hard it was to get strong perform...

What better way to start the new year than with Words of Wisdom? For the second installment of our blog series featuring interviews with science managers, we...

Through fall season, Harvard hosts a Science & Cooking course, where science topics relevant for cooking such as soft matter, organic chemistry, heat tra...

Basic project management often begins with a charter—a set of agreements that define the rules and expectations for team collaboration. I believe a team char...

Lazy blogging. I don’t want to reblog a topic someone else just did. So I will just point people to this interesting piece on should students teach? at Conde...

In my journey to expand my knowledge from physics to effective management practices, I maintain a steady, yet unhurried reading pace. I find the experience e...

Recently I have written posts on the challenges and subtleties of keeping a healthy funding stream for a scientific team. We have also covered some creative ...

As a research manager, securing stable funding for your group is a critical responsibility. Your team, whether students or professionals, relies on you as th...

Starting a new blog series at Set Physics to Stun! While most of my posts are based on my own experience, observations, or creations in science and scientifi...

A (total!) eclipse, travel, and hackathons have slowed down my blogging. That together with, for the first time, being asked to do the technical review of a ...

A busy week of teaching and preparing for an upcoming trip to Quebec to witness the eclipse left little time for blogging. Nonetheless, I’ve been mulling ove...

This post tells a bit of my own professional story as I left life as a pure researcher, and then moves toward introducing my first managerial tool for scient...

As I keep trying to create technical content, columns on Nature continue to interrupt me. Seems like these really are good sources of inspiration.

While I was working on a much more technical first post, Nature released a News article on a core raison-d’être of this blog: the trust of public in scientis...

This is it, I can’t believe I am finally starting this! Welcome to “Set Physics to Stun”, my blog on physics, scientific management, and other topics relevan...