Improving How Universities Teach

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

Through fall season, Harvard hosts a Science & Cooking course, where science topics relevant for cooking such as soft matter, organic chemistry, heat transport, and diffusion, are discussed. This course is often accompanied by a series of public lectures working as an outreach activity to engage the lay community.

In this public lecture series, reputed chefs are brought to a stage shared with a physics or chemistry Harvard instructor (at times known as a preceptor…Harvard culture has funny local jargon for reasonable widespread terms…), and the audience is stimulated to participate and engage in various ways. This year, in particular, the instructors of the course opened the opportunity for audience participants to share term papers and join in the course science fair with the students actually taking the full class.

Well, I am into cooking, and into science, and into challenges. So me, my wife and a friend (who all share some of these passions) decided to get together and pursue a small joint project. So for the first bona fide science post of Set Physics to Stun, I bring you the project we submitted to the class and science fair. The results were built on some good 10 hours of efforts in a kitchen and analyzing data on recipes for Brazilian pão de queijo.

Lisa Lin, Pedro Lopes, Marianne Moore

In a cook-out get-together in October 2024, the present authors attempted a pão de queijo recipe from Alex Atala [1]. While the cheese puffs tasted fine, the texture of the crust did not correspond to the memories of one author who grew up in Brazil; the breads felt too dry, and the crusts too thick. Following the Harvard’s Science and Cooking public lecture series a few weeks later, we were led to consider the effects of heat (water) diffusion into (out of) pão de queijo, and what factors might govern its texture.

Though pão de queijo is naturally gluten-free and uses only tapioca starch, we found evidence suggesting that the varieties of tapioca starch used could be relevant. Most commonly mentioned were the effects of using sweet (unfermented) versus sour (fermented; polvilho azedo, henceforth referred to as azedo) tapioca starch, with the former contributing to denser crumb and the latter to a more open and elastic crumb [2][3]. In our original recipe, we used a mix of azedo (from Brazil) and sweet tapioca starch from Thailand (henceforth referred to as Thai starch), and some references also claimed a noticeable difference between sweet Thai tapioca starch and sweet tapioca starch produced in Brazil (polvilho doce, henceforth referred to as doce)[4]. Though this author attributed the result to the fineness of the milling, tapioca starch does not contain broken-down grains like regular flour, but rather just semi-crystalline granules of amylose and amylopectin that are typically extracted by filtering out any solids from the cassava root itself [5]. Despite having different textures, we believe that a more meaningful difference between Thai and Brazilian starches could be at play.

Rather than milling, we believe hydration plays a more significant role in the difference between Thai and Brazilian tapioca starches. In particular, the latter has a moisture content of around 45% [6], leading to its characteristic granularity in contrast to the fine texture of the former, which typically has a moisture content of around 13% [7]. One of the authors knows from experience that, upon further hydration, sifted Thai starch can be substituted for doce to good effect in recipes such as tapioca pancakes (beiju). Ref. [4] provides pictures comparing Brazilian cheese puffs made from Thai and azedo starches, but does not compare results using Thai and doce starches, leaving this hypothesis open to test. In wheat bread literature, the importance of starch gelatinization and retrogradation is well documented for different ingredients [8][9]. Given that the rise in bread is partially due to evaporation of water within the dough when exposed to heat, we expect that pão de queijo made from Brazilian tapioca starch, with its higher moisture content, will rise higher than pão made from Thai tapioca starch.

Pão de queijo has unquestionable popularity in its country of origin, Brazil, and this popularity is also growing internationally. Methodically applying a scientific empirical analysis on the controlling factors on the texture of this delicacy can help clarify and inform lovers of carby, cheesy goodness of how to tailor different aspects of any pão de queijo recipe to their own tastes. In this way we hope to advance the appreciation of this cultural heritage by diverse audiences worldwide.

We investigate the effects of different ratios of sour to sweet tapioca starch on the thickness and texture of Brazilian cheese puff crusts. We also evaluate any potential discrepancies in the result by comparing Thai and Brazilian sweet tapioca flours.

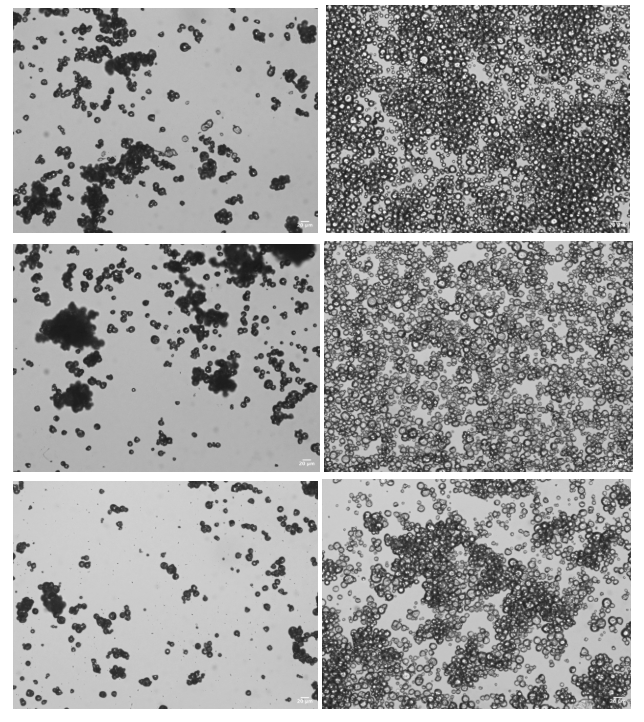

To give ourselves some intuition for how Thai and Brazilian tapioca starches would behave in a dough, we used bright-field microscopy to image the three starches we tested. The dry starch granules looked qualitatively identical at 10x magnification,, with perhaps lightly larger clumps in the doce starch (as could also be inferred by naked eye). On the other hand, mixing each starch with water in a ratio of 0.1 g starch : 200 ul tap water and imaging each sample on a glass slide covered with a cover slip revealed that the Thai brand starch granules absorbed water more uniformly than those of the Brazilian brands (1st image in right column, below), with kernels of undissolved starch still visible within the hydrated doce and azedo samples (2nd and 3rd images in right column, below). We thus expect doughs (and subsequent cheese breads) made from Thai starch to be smoother and softer than doughs made from Brazilian starch. In addition, granules of azedo flour tended to be least uniformly distributed throughout the liquid medium, leading us to expect the cheese breads made from azedo flour to be the driest and densest (as dense clumps would prevent the innermost starch granules from fully hydrating / gelatinizing).

From top to bottom, samples of Thai sweet tapioca starch, Brazilian sweet tapioca starch (doce), and Brazilian sour tapioca starch (azedo). Left column: dry sample; right column: hydrated sample. Scale bars correspond to 20 um.

From Alex Atala’s YouTube channel [1]. Ingredients:

Constants: We keep the quantities of milk, oil, salt, cheese, and egg constant. We use whole milk, canola oil, a mixture of cheeses (mozzarella, Gruyere, and cheddar), and large white eggs (about 50g each). Like Atala, we did not add table salt. We use previously unopened bags of starch from the following brands: Amafil (doce and azedo starches) and Three Elephants (Thai).

Our process was followed in a kitchen at 54% humidity, and 17ºC. We used the same kitchen scale for all measurements, which has an uncertainty of 1g, and the same ruler, assuming an uncertainty of 0.1 cm. We did not measure the temperature of the oven. Changing parameters: We change the ratios of sour vs normal cassava starch and compare Asian starch vs brazilian starch for the sweet starch:

| labels: | s | ib | ia | iib | iia | iiib | iiia | ivb | iva |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sour brazilian | 100% | 75% | 75% | 50% | 50% | 25% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| sweet brazilian | 0% | 25% | 0% | 50% | 0% | 75% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| sweet asian | 0% | 0% | 25% | 0% | 50% | 0% | 75% | 0% | 100% |

The labels indicate the pure sour starch dough (s), the series made with a ratio of Asian sweet starch (a), and another series with Brazilian sweet starch (b).

At several steps of the process, we took different measurements on certain properties of the different doughs and analyzed them. The data we collected can be found in the following Data spreadsheet.

Is Asian tapioca starch less hydrated than Brazilian starch or is the difference in texture of the powders just a result of milling?

By comparing weight and volume, we can estimate differences in water content for each starch. We took 5 measurements of leveled (and uncompacted) 1 tablespoon of each type of starch and averaged them.

| 1 tbsp of | Asian starch (g) | Brazilian sweet starch (g) | Brazilian sour starch (g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8(1) | 10(1) | 10(1) | |

| 8(1) | 9(1) | 9(1) | |

| 7(1) | 10(1) | 10(1) | |

| 8(1) | 9(1) | 9(1) | |

| 7(1) | 9(1) | 9(1) | |

| Average | 7.6 (0.4) | 9.4(0.4) | 9.4(0.4) |

Comparing the ratios of these average weights, we conclude that the Brazilian doce (sweet) starch is about 24% denser than the Thai starch. Though the Asian starch is finer in texture, the Brazilian one has more weight per volume, as one would expect for a higher water content in Brazilian doce flour. Assuming no difference in the original cassava species, we believe this indicates that the Brazilian sweet starch we chose is 24% more hydrated than the Asian one. This measurement corroborates our understanding that Brazilian tapioca starch is partially gelatinized and has a moisture content roughly 32% higher than Thai tapioca starch [8][9].

Note also that the density of the azedo (fermented) and doce Brazilian starches are the same. Assuming that the processing steps of these two starches are identical aside from additional fermentation of the azedo flour [10], then chemical changes from fermentation largely contribute only to differences in flavor of the starches.

Step 1. The Thai starch tended to clump together and stick to our measurement vessels, in contrast to the doce and azedo flours that did not compact together when measured and transferred between bowls. Jamming dynamics led Thai starch to often fly through the kitchen, across distances between approximately 5 - 10 cm.

Step 2. No flour mixing. No noteworthy observation.

Step 3. The scalding process felt different between samples from series “a” and series “b”. Generally, the doughs made from the Thai starch felt smoother and softer than those made from the sweet doce starch, which tended to be crumblier. The pure azedo batter, however, felt the crumbliest at this stage, as expected from our microscopy images.

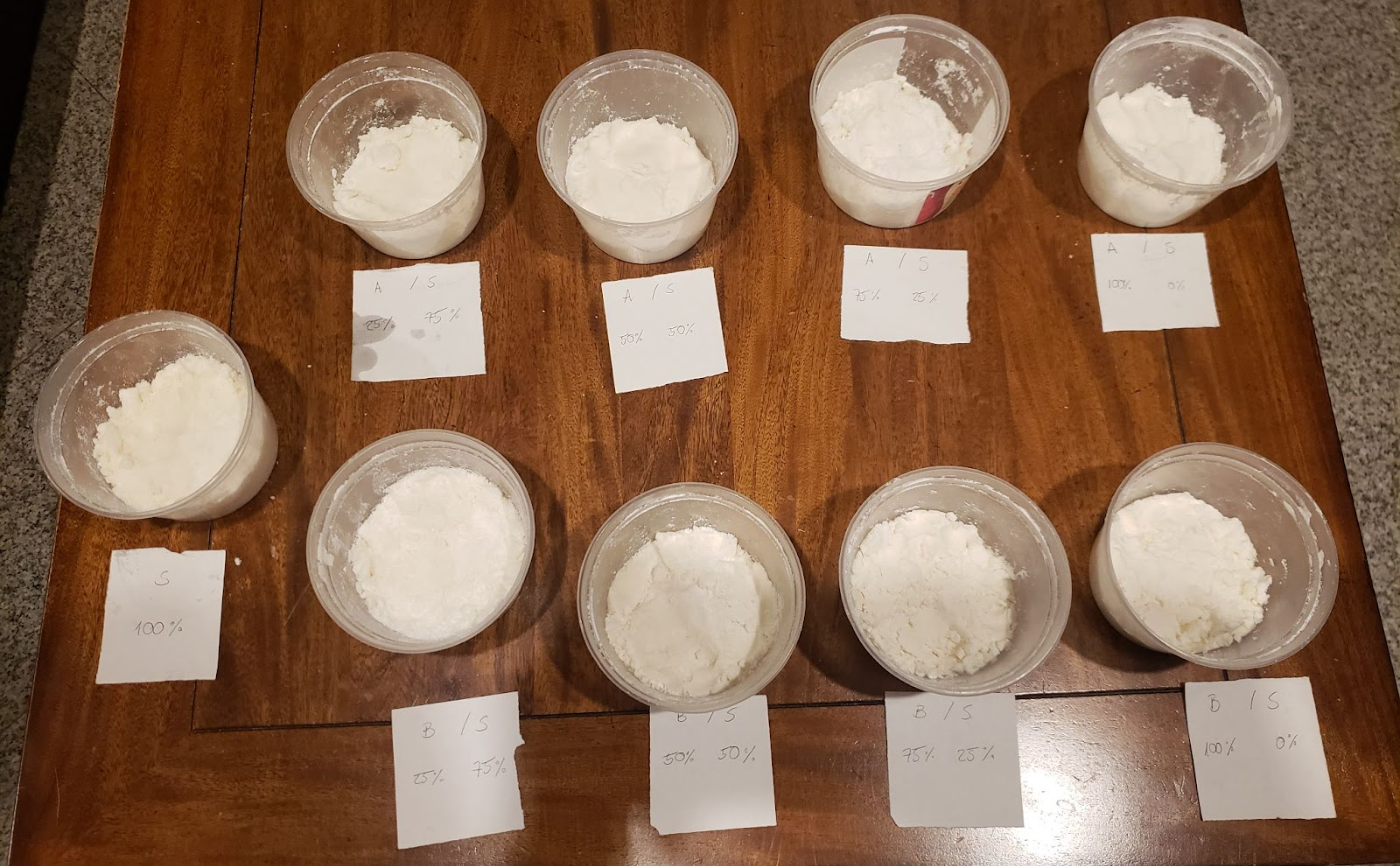

A photo of the different doughs prepared; S stands for sour, A for Asian Sweet Starch, and B for Brazilian Sweet Starch. The upper row contains the doughs from series “a” and the lower one from series “b”. The doughy texture from series “a” at this stage can be clearly seen and contrasted with the series “b” in the lower row.

Step 4. While all samples became well-formed doughs at this stage, some of the observations above remain applicable here as well. The pure azedo dough was firmer than the others, while the dough made with pure Thai starch felt the softest and smoothest and was easily distinguishable from the dough made with pure doce flour. All doughs made with the Thai starch (the doughs from the “a” series) had more visible white clumps of starch that aggregated in the previous stage and so did not gelatinize.

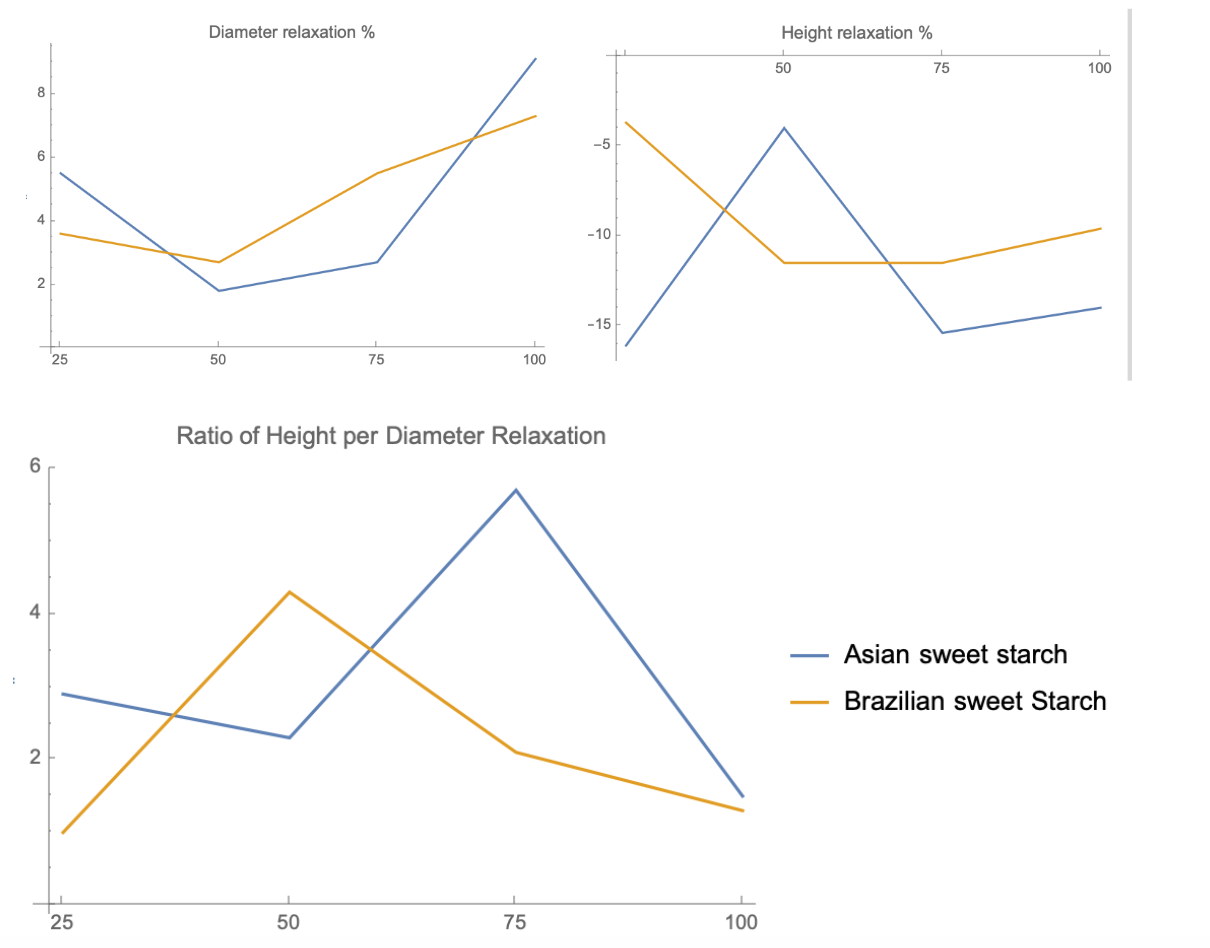

To provide a more quantitative evaluation of how easily the different doughs deformed, we shaped them into cylinders and placed a 3.58kg mortar on top of them for 10 seconds. We then compared the height and diameters before and after weighing, removing the weight before taking our final measurements - these measurements are not in the linear deformation regime and evaluate plasticity rather than elasticity. The doughs often deformed differently across an axis due to misplacement of the mortar weight, so we took averages of the shortest and highest deformations, and always measured diameters transverse to the axis defined by shortest and highest height deformations.

Computing the (negative) ratio of changes in height to changes in diameter of these cylinders gives us a quantity related to the (inverse) Poisson’s ratio, a metric for the deformation (expansion / contraction) of a material perpendicular to the direction of applied stress. All of them are positive, as expected, as the cylinders expanded outwards when compressed vertically. We recorded no change in diameter for the pure azedo (sour starch) dough, whereas we did record a nonzero change in height; as this was likely due to a measurement error, we discarded this data point.

Above we show plots generated comparing compression measurements for dough made using Thai starch and those using Brazilian sweet starch (doce) (error bars not included). The x-axis labels the percentage of the corresponding sweet starch in each dough. We had expected deformations to be of similar magnitudes when the amount of sour starch dominated over either sweet starch for both cases, and to diverge as the amount of sweet starches increased. In the end, more replicates and a more precise measurement procedure would be required to fully extract such a trend, if one exists. While dough made from Thai starch tended to flatten more along the height axis, our data measuring the increase in diameter (“diameter relaxation”) of the dough cylinders is somewhat inconclusive, with Thai and doce starches deforming more or less than each other depending on the percentage of sweet starch in the dough. At the extreme, dough made purely with Thai sweet starch tended to deform more along both vertical (height) and diametral axes than dough made with pure doce (rightmost data points of the top two plots), as we would expect from our previous observations that the Thai starch absorbs water more quickly and forms a softer dough.

Despite differences in the absolute axial and radial deformations of the doughs, the ratio of the plastic deformations of the doughs made purely with sweet starches converge to similar values independently of the origin of the starch (Thai or Brazilian; rightmost data point). One might expect this to mean that both doughs would behave similarly in the cooking process, though our previous notes regarding water absorption properties of the starches would suggest otherwise. In summary, our results suggest that doughs made with Thai starch are more deformable than those made from Brazilian starch, given that the former flatten around 5% more than the latter.

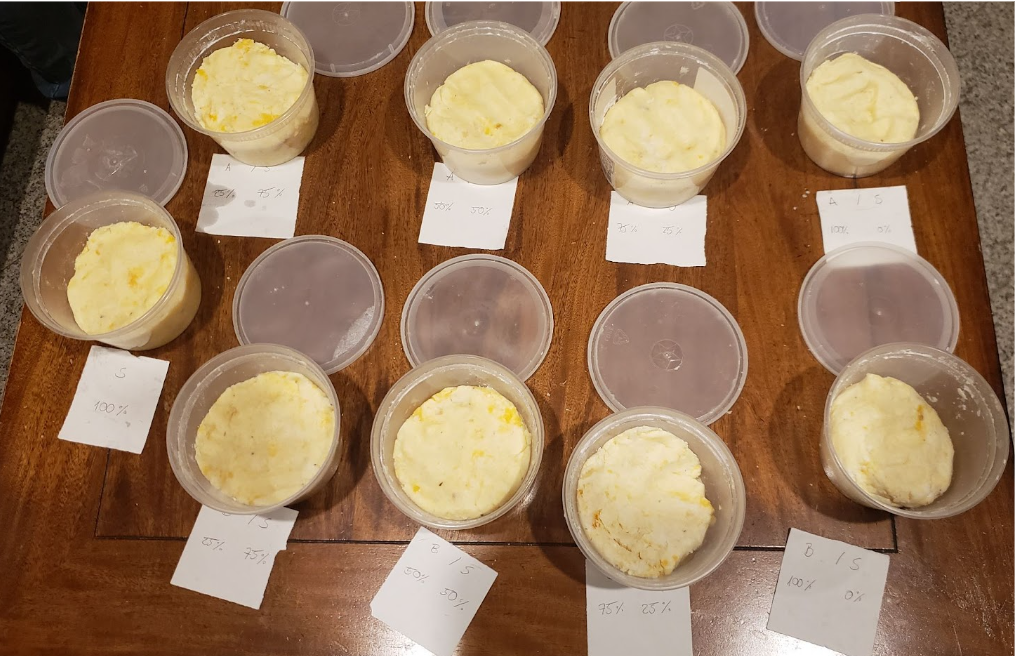

Same photo as before, but post-processing by adding eggs and cheese. All samples acquire a doughy texture, albeit the “a” series feeling smoother

Step 5. We shaped 4 balls of 32g each for each dough type for baking. We sprayed the oven with water to increase humidity (according to AI, this factor that should lead to thinner crusts [8]). According to our qualitative observation, sample series ib (75% Brazilian sweet starch) felt the hardest to shape.

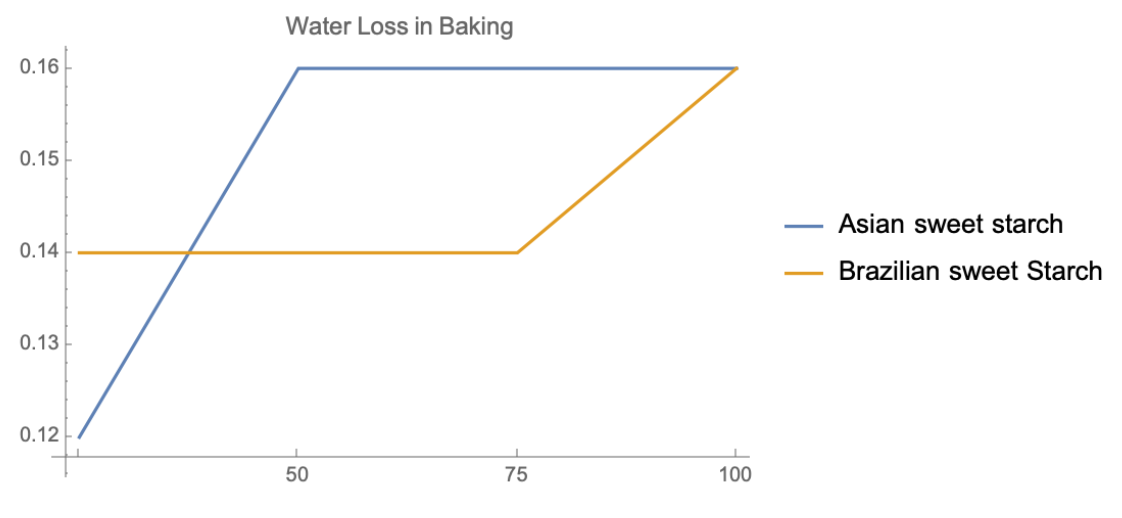

Step 6. After baking we took measurements of the weights of all samples to evaluate water loss, cut samples in half vertically to evaluate the thickness of the crust, and took note of the crumb of the cheese breads. Our analysis indicates that, independently of the starch used, the breads lose about 15% of their weight due to baking (32 g to 28 g), with higher losses for higher concentrations of sweet starch. Breads made with Thai brand sweet tapioca starch tended to lose more water than those made with Brazilian sweet starch. This is surprising to us given the lower water content of the Asian sweet starch, but perhaps this means that the Brazilian starch has better water retention capacity. A potential explanation for this lies in the dense clumps of

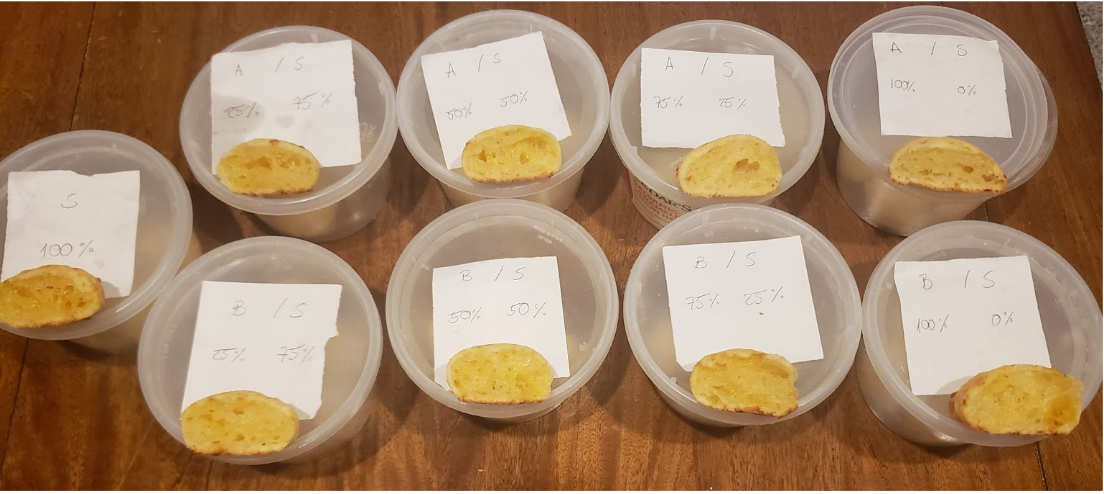

The figure above shows cross sections of our end products. Qualitative analysis of the outcomes led us to inconclusive remarks on trends, except for the sensorial observation that we should probably have included salt in the dough (which however might depend on the choice of cheese). The most noticeable effect is the flatness of the pão de queijo made by purely using Asian sweet starch (top right), which had been previously reported in Ref. [4]. Surprisingly, we unanimously felt that the recipe made purely with Brazilian sweet starch (bottom right) felt the airiest, opposite to the widespread belief that pure sour starch should lead to the lightest result [2][3]. One last, unsurprising, observation is the lack of sourness in the taste of recipes with less than 50% sour starch.

We estimated crust thickness using a ruler. All trials produced a crust of about 1 mm thick, set at around 15-20 minutes of cooking and resulting in a heat diffusion coefficient D ~ 0.01 mm^2/min. The dough made from 100% doce flour had the thinnest crust, we estimate around 0.5 mm, but our tools lacked the resolution to more precisely quantify these differences. Qualitatively, the crunchiness and dryness of the crusts decreased from the pure sour “s” sample (driest, crunchiest) towards doughs with more sweet starch. Pães de queijo made from at least 75% sweet starch (either variety) felt less dry and softer (i.e. easier to chew). This may indicate that the sour (azedo) starch absorbs more water than the others.

We baked the cheese breads in columns of four (four samples per trial) across two baking sheets, baking one tray at a time in the center rack of the oven to allow for more even heat circulation. However, since we baked multiple trials on the same pan, hot / cold spots within the oven may have contributed to some of our observations in the finished products.

The bottom of the pães de queijo tended to have a thicker crust than the tops. This aligned with our expectations that the surface area in more direct contact with a heating element (i.e. the heat-conducting metal pan) experienced greater heat transfer while baking and thus dried out to a greater extent than the crust exposed to the air, resulting in a thicker crust.

Here were our final verdicts on the extreme cases:

100% azedo: chewiest, hardest, flavorful but sour flavor may be too strong for some

100% doce: flavorless, thinnest crust, airiest

100% Thai starch: flat, chewy, spread out the most

Overall, we recommend using a combination of doce and azedo starches; the large air bubbles in the doce starch contribute to a light and fluffy texture while the azedo starch contributes flavor and structure. While our experience with the doce starch is somewhat at odds with other descriptions of it as contributing denseness and chewiness to the finished product, we believe our results can still be used as guidelines to help determine what combination of starches will achieve the most pleasurable texture for bakers looking to up their Brazilian cheese bread game.

For those interested in pushing our preliminary exploration here further, there are many avenues left to consider. Testing how moisture, fat content, and oven temperature affect the dough are natural next steps. In analogy to bread-making, higher hydration bread doughs may lead to thinner crusts and more open crumbs [11][12]. The tests we documented here could easily be attempted on blender recipes for Brazilian cheese bread [13], which naturally contain more liquid ingredients and are usually baked in a muffin pan to help set the shape of the breads. From our results above, we know that the different starches tested have different absorption properties of water. This observation is corroborated anecdotally - the best pão de queijo that one of us has had was with 100% azedo starch in a blender, resulting in a spongy bread with a slight chew, a drastically different outcome from what we observed in our experiments above with a drier dough. (this observation is strongly challenged by the purist opinion of our Brazilian author! But the whole point or our work is to determine how the recipe can be varied to please different palates and cultures)

We did not measure the temperature of our oven, but it is often the case that the temperature listed on the oven does not correspond to its actual temperature. Oven temperatures also tend to fluctuate considerably whenever the oven door is open, and it can take several minutes for it to subsequently get back up to temperature [14]. Oven temperatures also often require significant amounts of time to preheat to the specified temperature, even after the oven itself says it has finished preheating (this is what happens if you bake two trays of cookies in quick succession and find that the second tray bakes faster). Thus proper regulation and variation of the oven temperature using an oven-safe thermometer could provide valuable insights into how temperature affects crust thickness and texture.

We tasted and made observations on the crust texture of our Brazilian cheese breads within 2 hours of them being finished baking; however, a test of good pães de queijo is whether they remain moist and chewy over time. To test this, interested individuals could log observations after leaving the breads in a sealed container after baking so that humidity is retained during retrogradation, as often is the case when they are left inside heated displays in Brazilian cantinas. We expect cheese breads with thicker crusts to be drier and soften to a lesser extent than those with thinner crusts, given that more moisture from the bread interior is required to hydrate and soften a thicker crust than a thinner one.

Fat acts as a preservative, and the fat content in the cheese bread can also contribute to how well it holds up texturally over time. Browning of the cheese breads is intimately related to the breads’ fat and sugar content due to the Maillard reaction, so we would expect that given a fixed temperature, breads with more fat would require a shorter bake time (or alternatively, would be more easily overbaked, leading to a thicker crust). Fat can be controlled in a variety of ways here - fat / water contents of different cheeses vary, so different types of cheese may result in different textures, crumbs, and crust hardnesses; similarly, modifying the ratio of milk to water in the dough may give rise to denser or lighter final products with softer or harder crusts (given constant cooking time).

[1] Alex Atala’s pão de queijo recipe

[2] Panelinha’s pão de queijo recipe

[3] Reddit

[4] Serious Eats Brazilian cheese bread recipe

[5] Ziyu Wang, Pranita Mhaske, Asgar Farahnaky, Stefan Kasapis, Mahsa Majzoobi, Cassava starch: Chemical modification and its impact on functional properties and digestibility, a review, Food Hydrocolloids, Volume 129, 2022, 107542, ISSN 0268-005X, DOI.

[6] Olivier François Vilpoux, Marney Pascoli Cereda, Chapter 9 - Traditional Brazilian foods based on partial gelatinization of cassava starch: tapioca pearls (“sagu”), Brazilian tapioca (“tapioquinha”), broken tapioca pearls (“tapioca”), and popped tapioca pearls (“farinha de tapioca”), Editor(s): Marney Pascoli Cereda, Olivier François Vilpoux, Starch Industries: Processes and Innovative Products in Food and Non-Food Uses, Academic Press, 2024, Pages 211-232, ISBN 9780323908429, DOI.

[7] Evaluation of the moisture content of tapioca starch using near-infrared spectroscopy. Kittisak Phetpan and Panmanas Sirisomboon. Journal of Innovative Optical Health Sciences 2015 08:02. DOI.

[8] Nathan Myrvhold’s blog (Modernist Cuisine).

[10] Tapioca starch processing.

[11] King Arthur Flour article on dough hydration.

[12] Baking Science article on dough hydration.

[13] Blender pão de queijo recipe.

[14] The Kitchn article on oven temperatures.

[15] Wikipedia page on starch.

[16] Bakerpedia.

[17] Chat GPT.

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

Back to book reviews! The backlog is growing!

This post is a long one in the making. I should dedicate it to my wife, as this has been a family project running for years. We will divert from science mana...

Short post inspired by a big lesson. Recently I was in a conference and me and other scientists were discussing how easy or hard it was to get strong perform...

What better way to start the new year than with Words of Wisdom? For the second installment of our blog series featuring interviews with science managers, we...

Through fall season, Harvard hosts a Science & Cooking course, where science topics relevant for cooking such as soft matter, organic chemistry, heat tra...

Basic project management often begins with a charter—a set of agreements that define the rules and expectations for team collaboration. I believe a team char...

Lazy blogging. I don’t want to reblog a topic someone else just did. So I will just point people to this interesting piece on should students teach? at Conde...

In my journey to expand my knowledge from physics to effective management practices, I maintain a steady, yet unhurried reading pace. I find the experience e...

Recently I have written posts on the challenges and subtleties of keeping a healthy funding stream for a scientific team. We have also covered some creative ...

As a research manager, securing stable funding for your group is a critical responsibility. Your team, whether students or professionals, relies on you as th...

Starting a new blog series at Set Physics to Stun! While most of my posts are based on my own experience, observations, or creations in science and scientifi...

A (total!) eclipse, travel, and hackathons have slowed down my blogging. That together with, for the first time, being asked to do the technical review of a ...

A busy week of teaching and preparing for an upcoming trip to Quebec to witness the eclipse left little time for blogging. Nonetheless, I’ve been mulling ove...

This post tells a bit of my own professional story as I left life as a pure researcher, and then moves toward introducing my first managerial tool for scient...

As I keep trying to create technical content, columns on Nature continue to interrupt me. Seems like these really are good sources of inspiration.

While I was working on a much more technical first post, Nature released a News article on a core raison-d’être of this blog: the trust of public in scientis...

This is it, I can’t believe I am finally starting this! Welcome to “Set Physics to Stun”, my blog on physics, scientific management, and other topics relevan...