Improving How Universities Teach

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

Back to book reviews! The backlog is growing!

Last year, I read a lot about management, trying to educate myself more on the topic and to connect with the lives of—and challenges faced by—scientists. In September 2024, I posted about the factors driving an individual’s motivation in a scientific team; the discussion was framed as a review of the book “Drive”, by Daniel H. Pink. This time we will expand the scope and consider what makes a team work well together. The inspiration for this post comes from reading The Five Dysfunctions of a Team by Patrick Lencioni.

The author is a well-known figure in private industry, coaching companies on organizational health and teamwork. He has written several books, many widely acclaimed. So, we should probably start with a disclaimer: the “sociological” theories in the book have found deep appreciation among several leaders and corporations, and have been built upon the author’s empirical experience—but, to my knowledge, they have not been rigorously tested using scientific methods. Still, human experience is quite valuable, and the thoughts in the book definitely got me thinking.

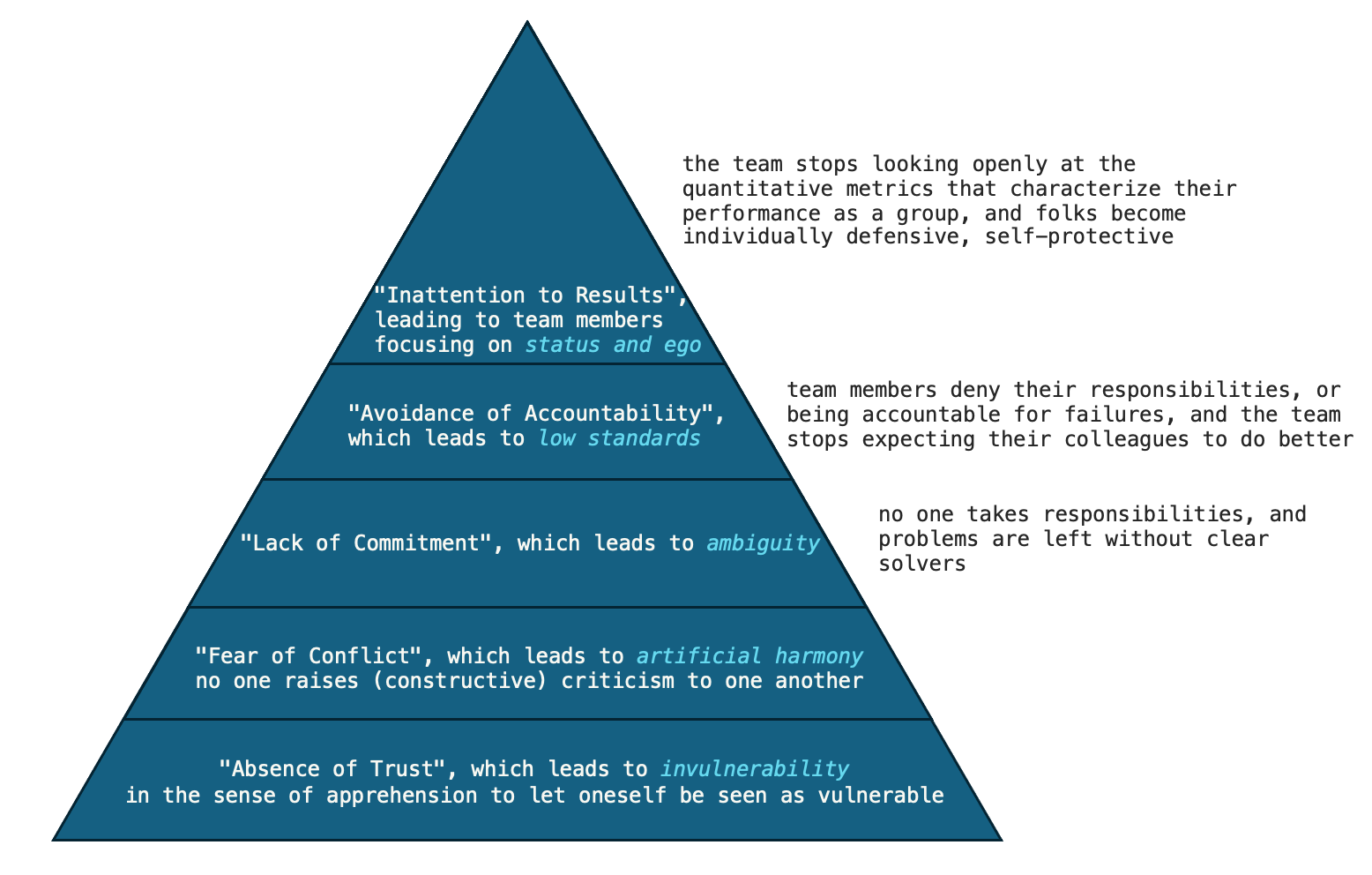

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team is mostly composed of a long story in which the author role-plays (a common practice in business training, I’ve come to learn) characters navigating team conflict within a company. They are somewhat saved—or at least set on a path toward progress—by a new CEO who has mastered the concepts behind team dysfunction. The author then re-describes these ideas in detail. The five dysfunctions are presented in a causal relationship, where each layer serves as a scaffold for the next:

Again with the disclaimer that this was not presented as a scientifically verified psychological process, I gotta say I can quite relate to this perspective.

Looking at modern science in general, it’s rare for individuals to work entirely alone. They exist, but they don’t represent most of the statistics. In my own scientific collaborations—and from observing those of colleagues—I’ve often seen teams exhibit some degree of dysfunction that can fits the pattern above. Here are some signatures that some may relate to:

I hope the language above makes it clear that these examples are not biased toward any particular group of scientists: they can occur among trainees and students, managers and supervisors, and in virtually any field of science.

What is the onset of these dysfunctions? The author doesn’t say much about how they begin, and I believe that characterizing early warning signs of dysfunction—or signs that a team is headed down that path—could be very important. In science, I dare say much of this can arise from overcommitment to too many activities. The workload of science managers can be extreme, and the path of individual contributors often resembles a random walk. Haste and pressure can lead to mismanagement and miscommunication. The often present high degree of freedom in scientific environments, without proper management, can also easily lead to ambiguities and individualism.

The author also emphasizes (in a good attempt to sell another of his books) that not all people are capable of being team players, and that paying attention to certain virtues can help in hiring and fostering more productive behaviors. I don’t feel too comfortable to judge what others can or cannot do, but I think I see where the author is coming from, and I guess I like the advice.

On the pathway to solving such dysfunctions, the author highlights the importance of humility (“the most precious virtue and antidote for all sin”), which enables vulnerability and creates the possibility of trust among human beings—who he sees as naturally inclined to self-protection. If the pyramid model above holds, a approach to fix the problem is to erode it from the base—by entering into risky discomfort and building trust.

My backlog of book reviews is getting large. I hope I can make a dent in it. This year I’m moving my reading interests from management to philosophy of science, and it looks like reading will be slower; since the content is much denser, I may post revisions by chapter. In any case, stay tuned for more lessons learned from the literature!

Book Review – Improving How Universities Teach Science (Carl Wieman)

Back to book reviews! The backlog is growing!

This post is a long one in the making. I should dedicate it to my wife, as this has been a family project running for years. We will divert from science mana...

Short post inspired by a big lesson. Recently I was in a conference and me and other scientists were discussing how easy or hard it was to get strong perform...

What better way to start the new year than with Words of Wisdom? For the second installment of our blog series featuring interviews with science managers, we...

Through fall season, Harvard hosts a Science & Cooking course, where science topics relevant for cooking such as soft matter, organic chemistry, heat tra...

Basic project management often begins with a charter—a set of agreements that define the rules and expectations for team collaboration. I believe a team char...

Lazy blogging. I don’t want to reblog a topic someone else just did. So I will just point people to this interesting piece on should students teach? at Conde...

In my journey to expand my knowledge from physics to effective management practices, I maintain a steady, yet unhurried reading pace. I find the experience e...

Recently I have written posts on the challenges and subtleties of keeping a healthy funding stream for a scientific team. We have also covered some creative ...

As a research manager, securing stable funding for your group is a critical responsibility. Your team, whether students or professionals, relies on you as th...

Starting a new blog series at Set Physics to Stun! While most of my posts are based on my own experience, observations, or creations in science and scientifi...

A (total!) eclipse, travel, and hackathons have slowed down my blogging. That together with, for the first time, being asked to do the technical review of a ...

A busy week of teaching and preparing for an upcoming trip to Quebec to witness the eclipse left little time for blogging. Nonetheless, I’ve been mulling ove...

This post tells a bit of my own professional story as I left life as a pure researcher, and then moves toward introducing my first managerial tool for scient...

As I keep trying to create technical content, columns on Nature continue to interrupt me. Seems like these really are good sources of inspiration.

While I was working on a much more technical first post, Nature released a News article on a core raison-d’être of this blog: the trust of public in scientis...

This is it, I can’t believe I am finally starting this! Welcome to “Set Physics to Stun”, my blog on physics, scientific management, and other topics relevan...